This Week In Football is a collection of some of the best in football currently outside the walls of AFL clubs or broadcasters. Each week a curated grab bag from regular contributors and special guests will provide insight into and beyond the game on subjects of their choosing. For more about our contributors, click here.

Banner images by Polly Porridge of the True Bloods Podcast. Check out her other design work.

Before the Bounce

It’s finally here.

After a long and grueling season the final men’s AFL game for 2025 is at our doorstep.

While there’s still a lot of great AFLW games left this year, a granny is special regardless of the level.

The match-up is a mouth watering one. In one corner stands the reigning premiers, the other the best team across the course of the year.

Just four quarters to sort out who will be crowned the champions of the year. Just four quarters of the most important footy of the year left to enjoy.

So make sure you are around the people you like watching the game with, in the place you like doing it the most (except if that place is the MCG if you don’t have tickets). Let’s hope we have a classic like 2018 or 2023 on our hands.

This week in football we have:

This will likely be the second last edition of TWIF this year. Closer to the end of the year there will likely be a TWIF Year In Review edition compiling the best of 2025.

Thank you sincerely to all those who subscribed, read, share and most importantly wrote for TWIF.

Grand final preview

Images – James Ives. Words – Cody Atkinson and Sean Lawson

This preview will contain excerpts of items Cody and Sean have written about

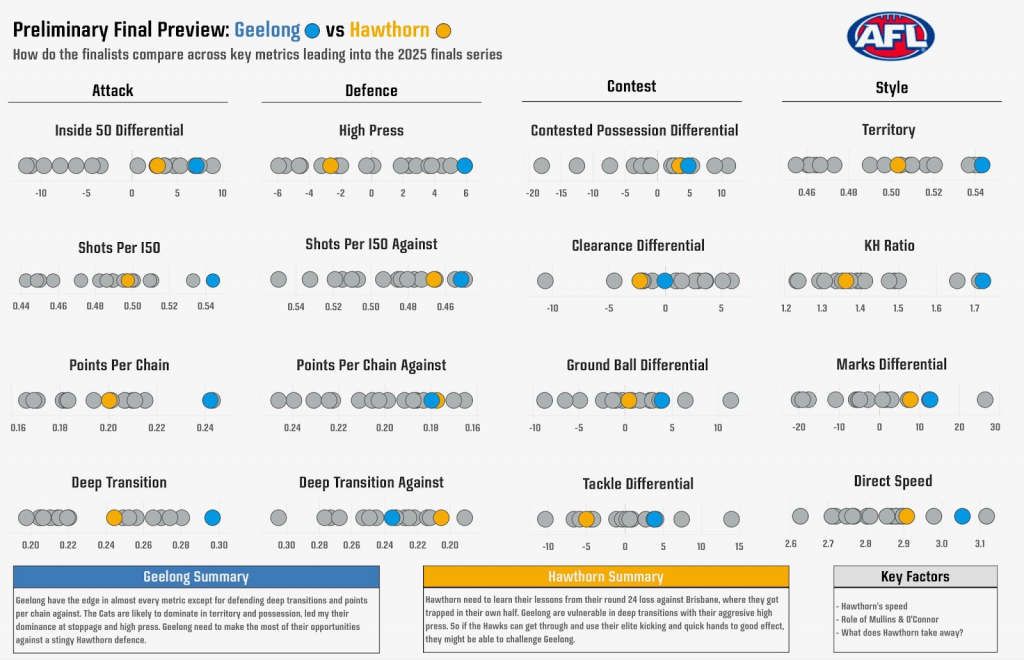

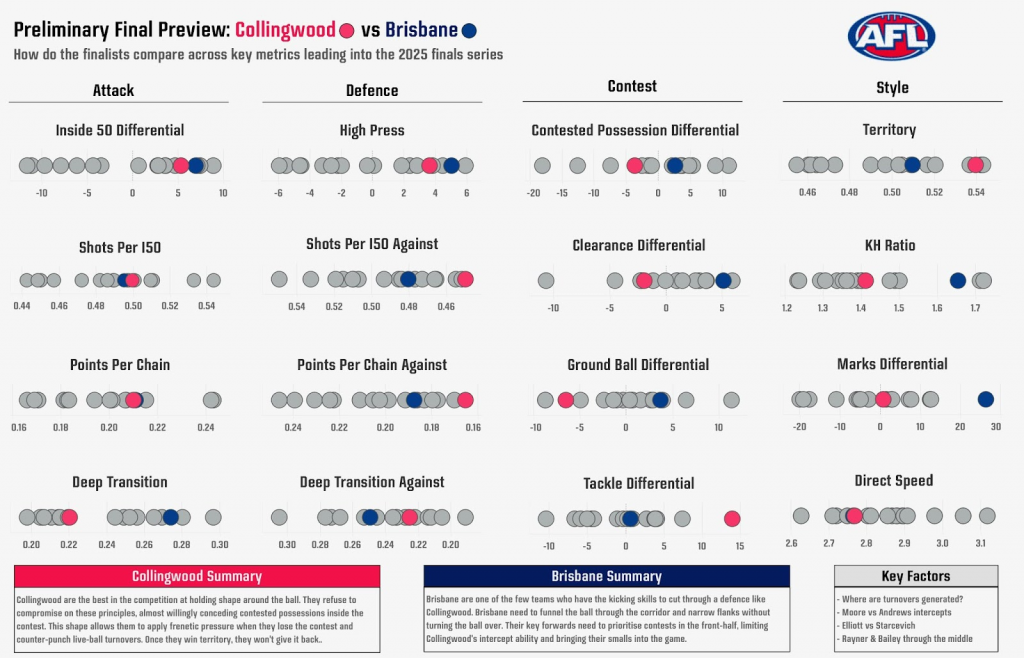

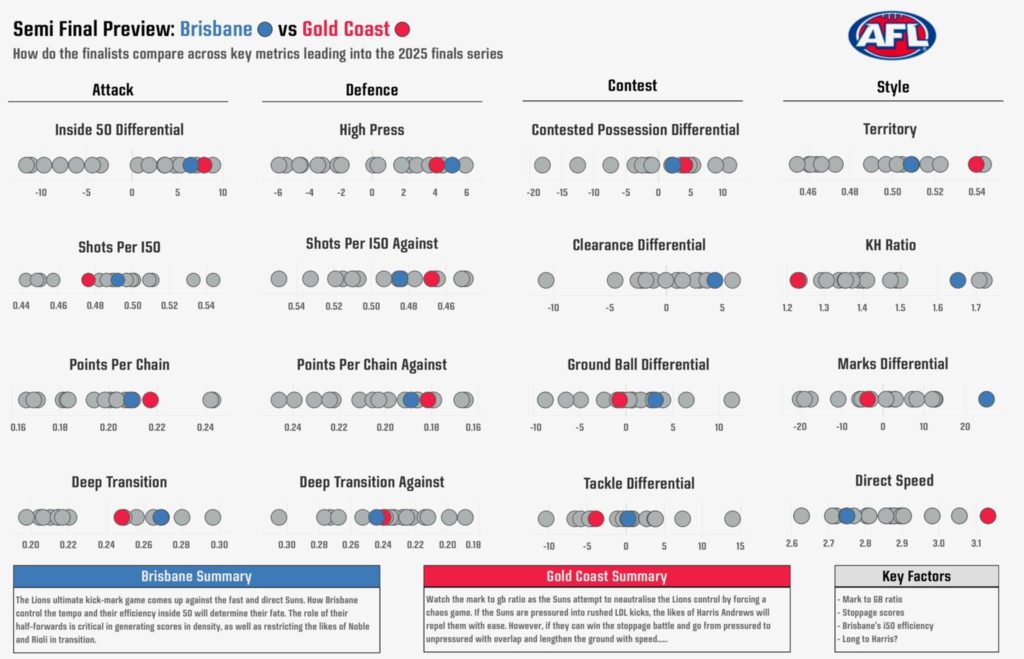

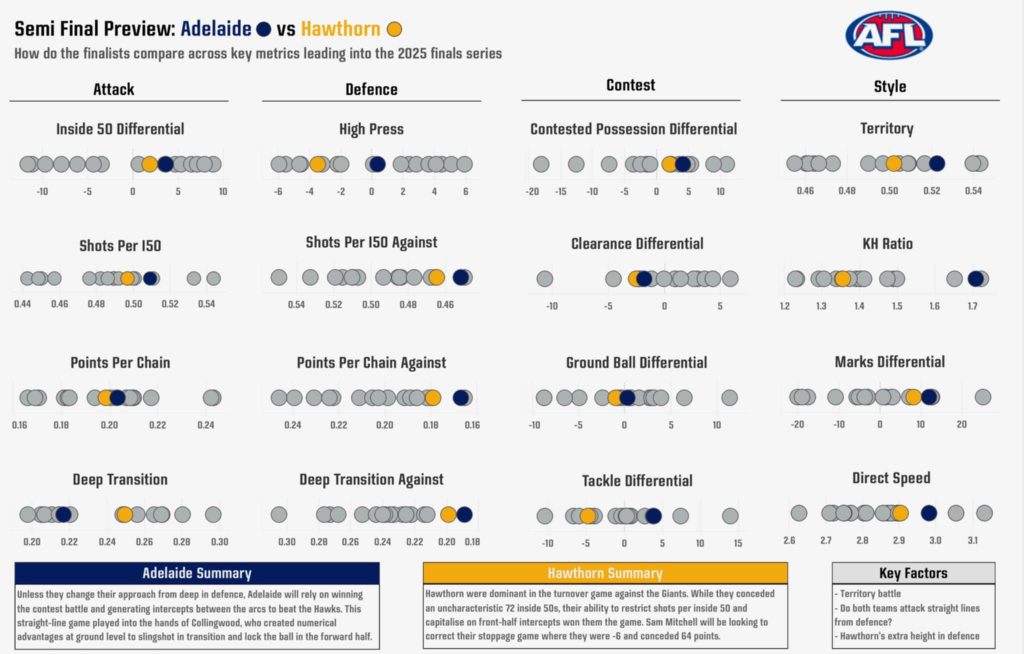

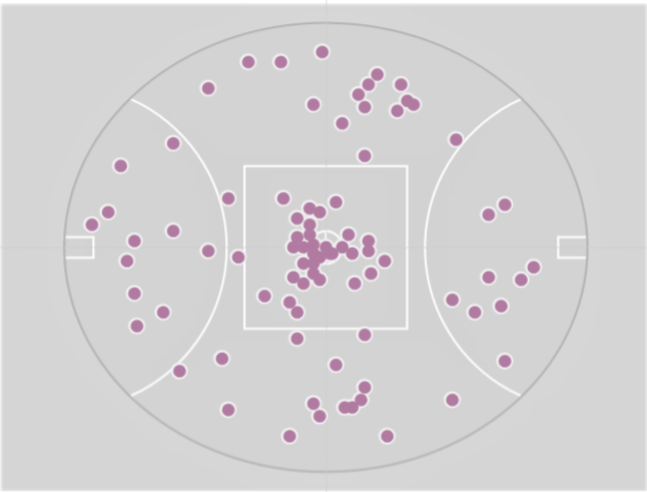

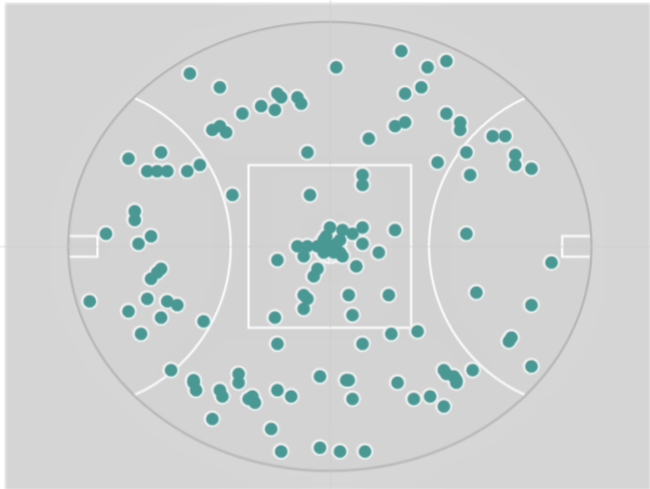

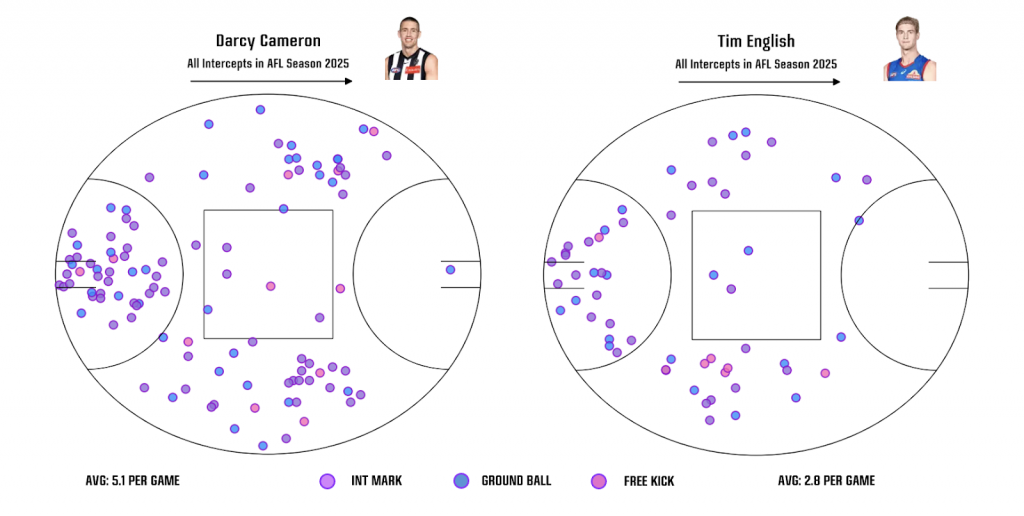

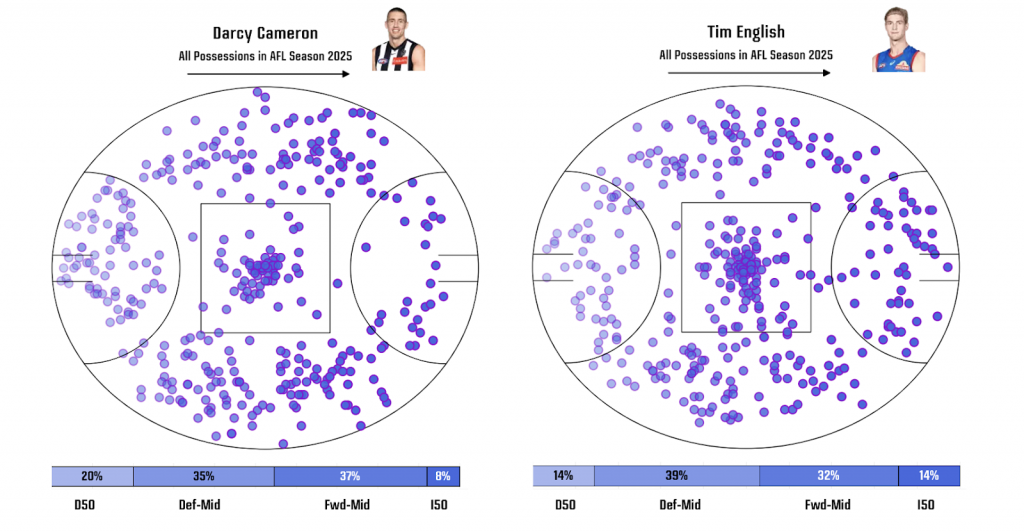

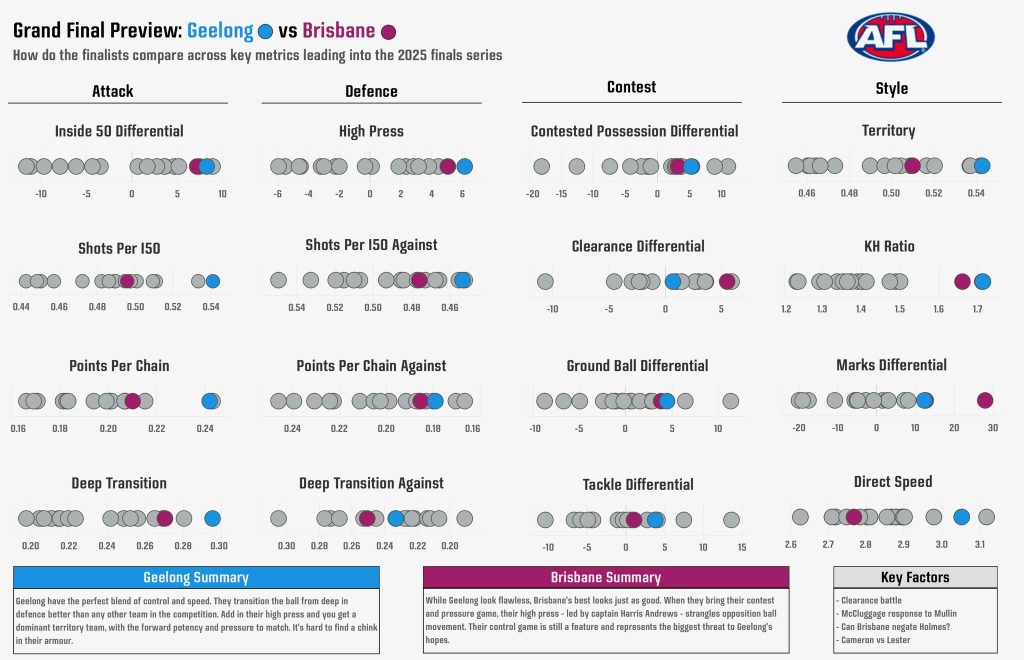

Similarities present themselves between the two sides. Both have a kick preference, and work best in the kick-mark game. Both press high for intercepts, and like to try to dominate territory to instead of maximizing efficiency.

A Lions game sees them controlling play by executing kicks to uncontested marks around the ground. No side takes more uncontested marks than the Lions, and only two prefer to kick rather than handpass more (Geelong and Adelaide).

There are differences however. The Cats play noticeably quicker than the Lions – with a few important caveats.

…This malleability is at the heart of the Cats’ success this year.

They switch up the speed at which they move the ball on a week-to-week basis as much as any other team.

The Cats can shift modes with ease and possess several core elements designed to put opposition sides off their game.

The Lions also try to establish the corridor as a cornerstone of their success.

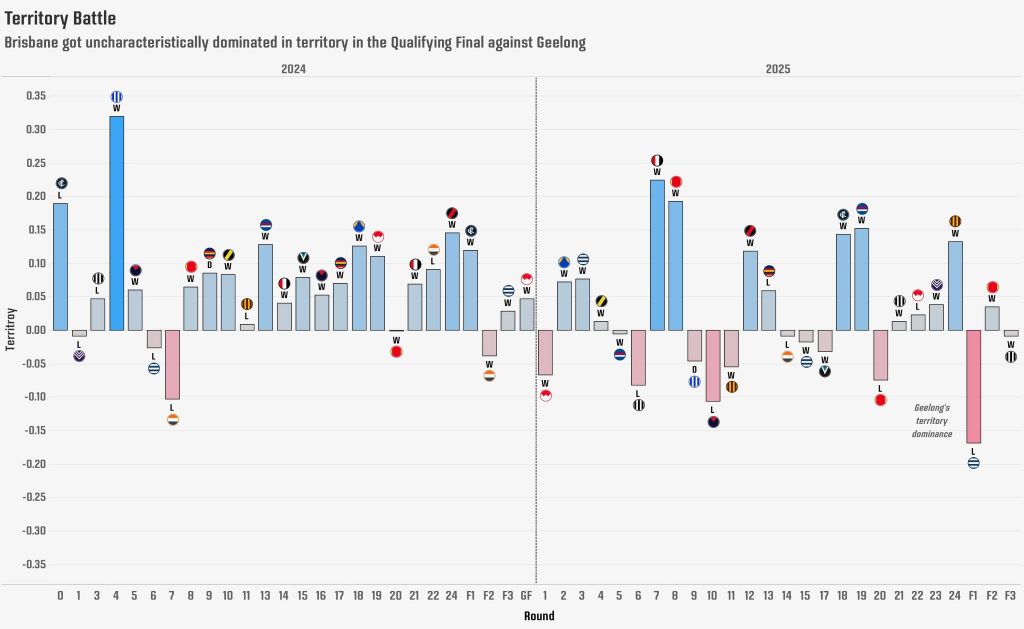

In their two wins against the Cats earlier this year, Brisbane forced the game through the middle about 50% more than an ordinary game. This opened the Cats defence up in a way that few other sides have been able to do this year. It’s also noteworthy that the Cats have struggled against the Giants, another side to target the middle of the ground.

In the qualifying final, the Cats went to a lot of effort to not only stop the Lions going through the middle, but to avoid the corridor themselves. When a side uses the guts of the ground it can also open you up for a quick counter attack the other way.

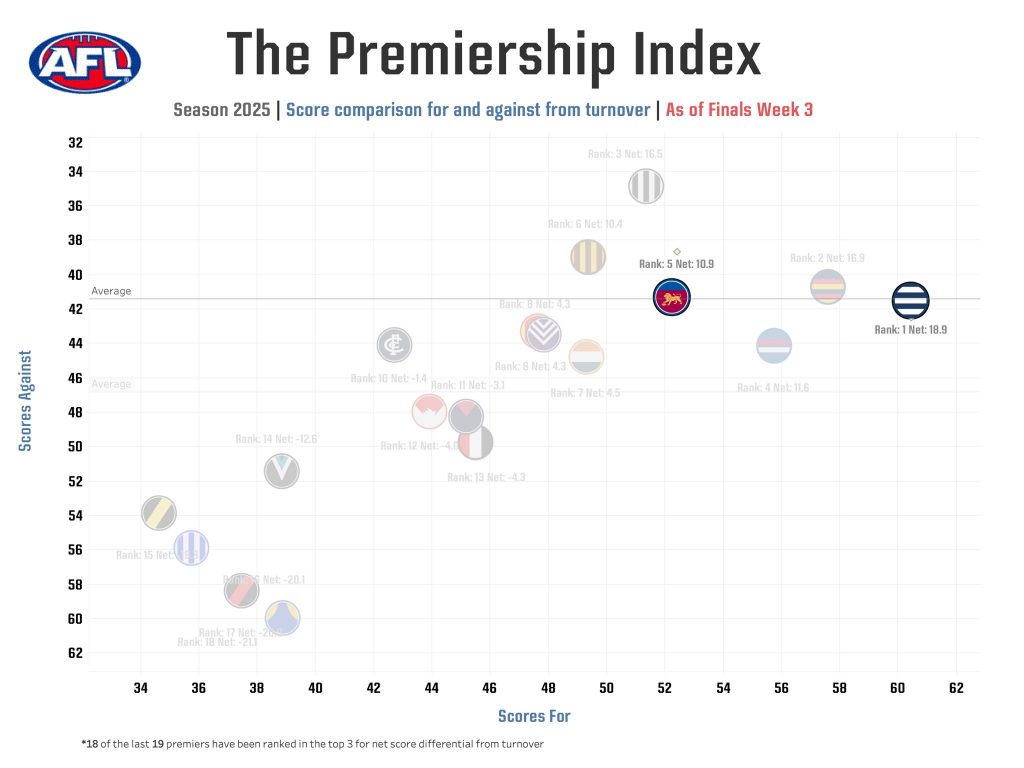

In every game of modern footy the turnover game is critical. About two thirds of scores come via turnovers. And no team is better at playing that game than the Cats.

No team is better at winning the ball and using it effectively than Geelong.

The Cats lead the league from scoring from intercepts across the course of the season.

Teams that have finished top three in total intercept scoring differential have won the flag in 18 of the past 19 seasons.

While the Cats lead the league in that number (by some way), Brisbane are only ranked fifth across the year.

The Lions need to get their clearance game working to get an edge.

Across the course of the year getting first possession — and the territory from it — has been key to how the Lions have succeeded. The Lions sit second throughout the season for clearance differential behind only the Western Bulldogs. Almost all of this advantage comes around the ground, with the Lions deep midfield group benefited by being able to deploy additional numbers around the ball.

In addition, getting reward from clearances is critical to their success.

Zac Bailey leads the league in scoring out of forward stoppages, but is far from the only contributor. Brisbane runs deep up forward, with a wide variety of first receivers and deeper targets.

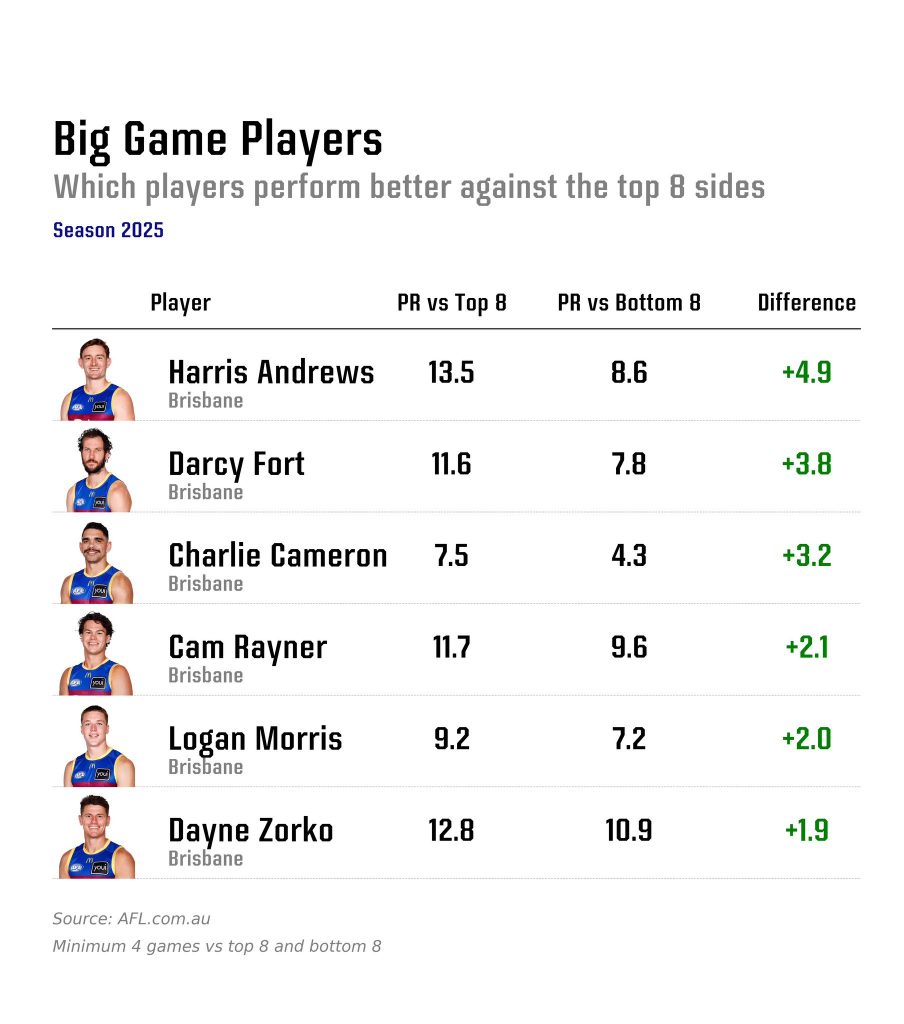

Both sides have players that step up in the big moments.

For the Lions their captain stands tallest of all, anchoring the side to (usual) victory. There are quite a lot of names prominent in the front half of the ground alongside the attacking Zorko. If the Lions are to win, one of these six will have a large part in the result.

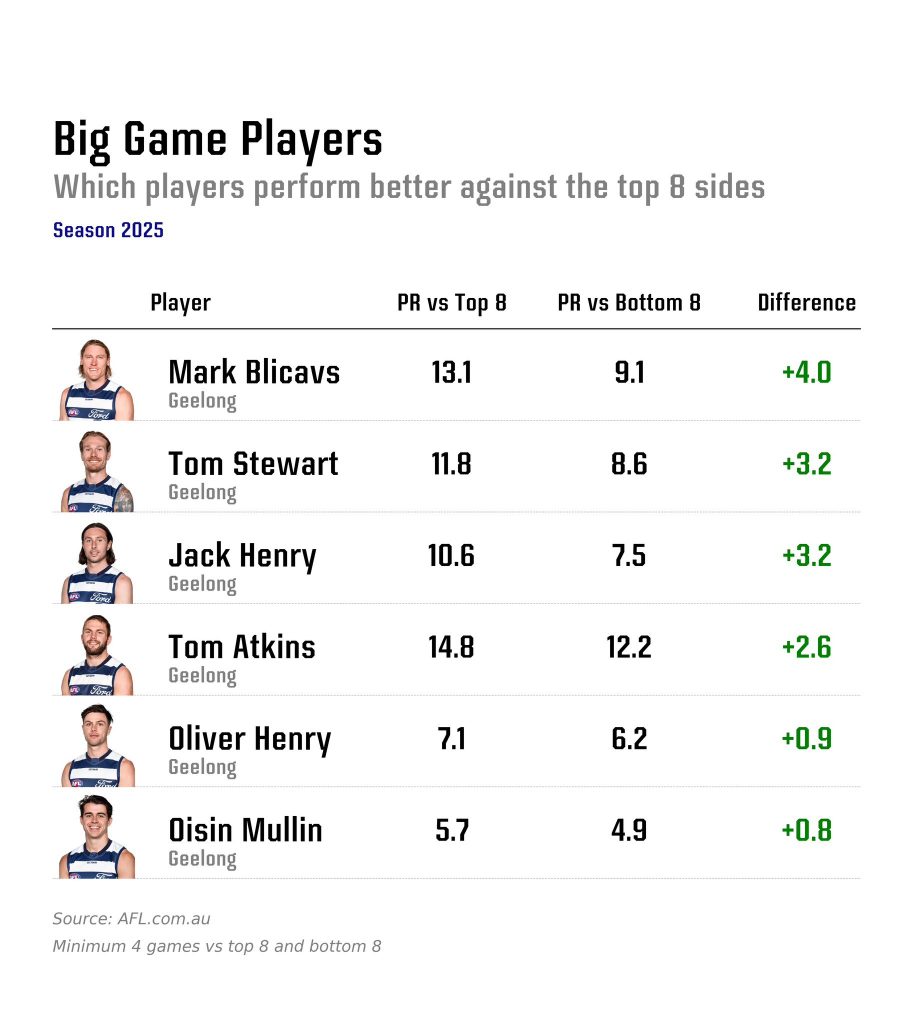

Mark Blicavs still doesn’t get the credit he deserves much of the time. The Cats are a much more even team against both good and bad sides. Noteworthy in this list is the presence of Tom Stewart who will miss the Grand Final with injury.

Now all that’s done, bring on the big game!

A Brief History of 129 years of the Cats and Lions

Emlyn Breese / CreditToDuBois.com

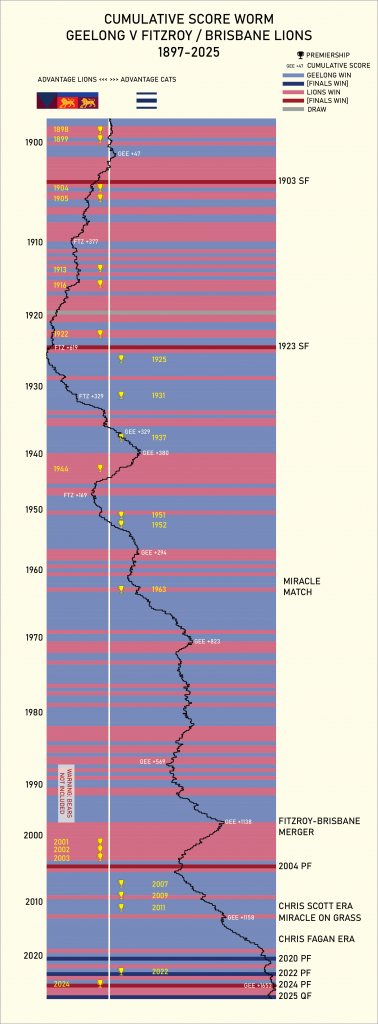

Given the upcoming Grand Final this week it’s worth taking a look at the cumulative results of our two grand finalists over the last 129 years of A/VFL competition. Instead of breaking down every match, this is a look at the result of ever game.

Think of it as a score worm like you’d see on the AFL Match Centre, but one that uses the endpoint of one match as the starting point for the next.

The Lions have been represented as a continuation from Fitzroy to the Brisbane Lions for the purpose of the main chart, but there’s a supplementary Brisbane Bears v Cats chart as well in the carousel below.

The history of the match-up has been broken into four eras with a very brief summary of each. To see each you can scroll through the interactive graphic to follow the history, or you can access at a separate standalone page here.

How the Grand Final lists were built

Sean Lawson

Brisbane and Geelong have been perennial contenders in recent years, but there’s a strong contrast in how the two grand finalists have built their lists.

There are broadly three ways clubs can acquire players.

The national draft is the primary conduit, where the most well regarded players must be selected in an orderly competitive process in their 18th year or later (overlooked players from previous drafts can be selected as well as some other caveats).

The second method is recruitment from other clubs. These are trades and free agency moves where there are conditions and reciprocal agreements required for a player to move are met. This is, again, a competitive process among clubs, who generally don’t like losing many of the players who request moves.

The third method is the various “freebies” pathways. These are for players who were basically available without much external cost having already been discarded or passed over. This includes the rookie draft, delisted free agency, international players and players “not from a football background”. These players could have been taken by anyone, with the challenge for clubs usually just identifying who is worth taking.

List formation is always a combination of recruiting pathways, but the Cats and Lions have done it very differently.

Geelong

If we can answer why Geelong have stayed in contention for two decades in a phrase, it is talent identification.

Geelong only have four native high draft picks in their grand final team, and only Jhye Clark was taken in the top ten.

They’ve also got a high quality trio of players pinched from other clubs in Patrick Dangerfield, Jeremy Cameron and Bailey Smith. All were arguably recruited partly for lifestyle reasons as well as due to the club’s sterling reputation. Rhys Stanley and Jack Bowes also came via trades – with the Bowes one particularly controversial as a generous Gold Coast salary cap dump.

But a few stars don’t make a team, and much of the Cats list, and much of their success, is filled out by players taken from obscure places. They have ten players who anyone could have recruited – six from rookie drafts, two delisted free agents in Stengle and Martin, and the two Irish imports.

Throw in relatively late picks like Miers and Humphries and we can say that nearly two thirds of this Cats team were recruited from savvy recruitment and talent identification that must have list managers across the league looking on with envy.

Brisbane

Before their current period of contention, the Lions languished at the foot of the ladder for most of the 2010s. During that time they stocked up on high draft picks.

The bulk of their team was built from the national draft, including six high draft picks. Rayner and McCluggage in particular are the sort of blue chip selections that paid off handsomely, essential to any good list rebuild.

They Lions have also been lucky enough to have three premium level father-sons, and several later selections came out of their academy in Andrews, Gallop and Marshall.

The balance of the Lions team has been made up of traded players, including Neale, Cameron and Dunkley who cost first round picks in their own right.

Only two Lions players came from “freebie” pathways, with both Reville and McInerney coming via the rookie draft. Reville isn’t strictly a “freebie” – he’s an academy pick who was prelisted by the Lions, but he was still overlooked at the National Draft.

The Lions have tapped many years of premium draft picks, and converted those selections into a formidable team.

Battle of the local talent

This year’s match-up features a number of hometown heroes on both sides, but also players who have crossed the borders too play for the other team.

Nine Queenslanders feature for the Lions, ranging from heavy hitters like Will Ashcroft, Dayne Zorko Harris Andrews to the fringe pair of Ty Gallop and Bruce Reville. Geelong are also fielding Jack Bowes, a Queenslander who began his career at the Suns.

On the flipside, Geelong have managed to secure a few quality local talents through the open draft, principally Jhye Clark and Gryan Miers, as well as rookie selections Tom Atkins and Jack Henry.

There’s surprisingly only one player lured “home” from another club, but Patrick Dangerfield is such a mammoth presence he is emblematic of the “go home” set by himself. Jeremy Cameron is a country boy too, but being from far flung Dartmoor, it’s a stretch to count him as a local.

Tackling the Brownlow

Joe Cordy

Matt Rowell’s Brownlow Medal win came out of nowhere, but with the power of hindsight it was also wholly in line with how the award has been trending.

The Suns’ defensively-minded inside midfielder doesn’t jump off the page in any of the typical metrics people use to predict how the votes are going to fall.

Rowell doesn’t regularly rack up massive disposal counts and he doesn’t make immediate obvious impact by foot with the disposal he does win. Even his highlights packages are pretty sparse for his standing in the game. These things are the domain of the pre-count favourite Nick Daicos, and his teammate Noah Anderson who was widely tipped to be the only Suns player with an outside chance of topping the vote tally.

What Matt Rowell does have is something that isn’t considered much by punters, or even the predictive models that have emerged in the last few years: he is constantly, visually, in front of the umpires.

With 61 free kicks paid against him and 53 paid to him, good for 1st and =4th across the league, Rowell was the only player to be directly involved in over 100 free kicks across the season with a final total of 114.

Australian Football is a physically exhausting sport to adjudicate, with field umpires running approximately 14km per game and boundary umpires 16km. Everybody knows this, but few people take into account the mental exhaustion.

The PGMOL – who are responsible for referees across English professional football – estimate their referees will make 245 decisions per game. In the NRL the estimate has been put around 400 decisions per game, and the NBA quote a range of 500-550.

In 2021 the-then umpires boss Hayden Kennedy estimated that in the 30 seconds of play around a stoppage, where possible infractions are at their densest, an umpire might have to make 10 to 20 decisions.

With a league average of 97.7 stoppages per game, that would put the decision count in a range of 977 to 1,954 decisions just around stoppages before even considering the rest of the game. Even with this mental load split between four field umpires, it’s a total that dwarfs most of their colleagues in other sports.

It makes total sense that when put in the position of having to decide who they thought the best three players were immediately following that gauntlet, while also being put in a Rawlsian veil of ignorance about the statistics of the game just played, the umpires continuously fall back on two main factors:

- who did I see a lot of, and

- who do I usually give votes to.

In the AFL era this burden has massively increased, even as the system stayed untouched since the early 1980s. Six votes split amongst three players for each game, decided on by the group of umpires on the day.

In 2025 there are more games, teams, players and therefore votes to be spread around the league than at any point in the AFL era. Despite that, the spread of distinct vote winners in a given season has trended consistently downwards over the last 35 years.

2025 had the narrowest field since 1990, with just 181 players receiving at least one vote. The previous record of 196 was set in 2024.

If you took a poll of every fan’s opinion of who the best player in the league was at the end of each season since 2020, I’d expect the most popular answers would be overwhelmingly Marcus Bontempelli and more recently Nick Daicos. Bontempelli’s window might well be closed, and despite having won an individual award every year of his career so far, Daicos was visibly frustrated with the reality of a third consecutive second place finish.

This isn’t because the umpires think either of these players are terrible despite the consensus of the wider footy community, Daicos’ 38 votes in 2024 would have won almost any other year in the award’s history. They’re just not the kind of players whose profile puts them at the front of the umpires’ mind week after week.

There’s been a lot of discussion in light of this and other controversial calls like Nasiah Wanganeen-Milera’s BoG snub to take the votes off the umpires, which I think is completely wrongheaded. Awards are only worth the importance the footy community puts on them, but that importance is built up over decades of history.

What makes it special is that it’s been awarded for over a century, and has been largely unchanged across that time. Even though the voting system has changed (albeit not in the last 46 years) it has always been determined by the umpires; taking it completely off them would effectively end that history, and even an award with the same name would have no real basis for comparison to anything in the 100 years previous to it.

There’s absolutely room for more Player of the Year style awards as the AFLPA and AFLCA have shown, and I believe there’s even room for another American-style MVP voted on by members of the football community from the media, clubs, and elsewhere.

The answer for how to move forward with the Brownlow however isn’t to completely kill it and give something else its name, it just needs to evolve with the sport. Give umpires time to recover from and digest the game they just saw, give them access to statistics and footage, and then ask for their votes in the cool light of day. The Brownlow is the most prestigious award in Australian Football and likely always will be, so there’s no reason to artificially constrain the people voting on it.

Poor Nick Daicos, polling exactly as expected

The Brownlow Medal is one of my favourite puzzles. The arcane voting methods and the lopsided sample sizes create a data science challenge that I’ve been enamoured with for the last couple years, and the 2025 certainly threw up some curveballs.

There’s a lot of different ways you can work out who will win the Brownlow. Some rely on their eyes, some on their gut and some on the best data available.

My chosen method of modelling the Brownlow is as follows:

- Train a XGBoost model on player based statistics. This includes Coaches Votes, SuperCoach, Fantasy, AFL Player Ratings, along with more basic stats like game margin, goals kicked, disposals etc. The model is a classification problem, using the training data from 2015 to 2024 to predict the likelihood of a player getting 3, 2 or 1 Brownlow Votes.

- From these outputs, a simulation is used to select players for each vote category per game. Once a player has been picked for 3 votes, they are excluded from the sample. This process is then repeated for the 2 and 1 vote. The entire process is then repeated for every game in every season 10,000 times. This should give us a good sample size for predictions, as each simulation will be independent, but weighted towards the higher expected vote getters.

So how does the model compare to the actual results on the night?

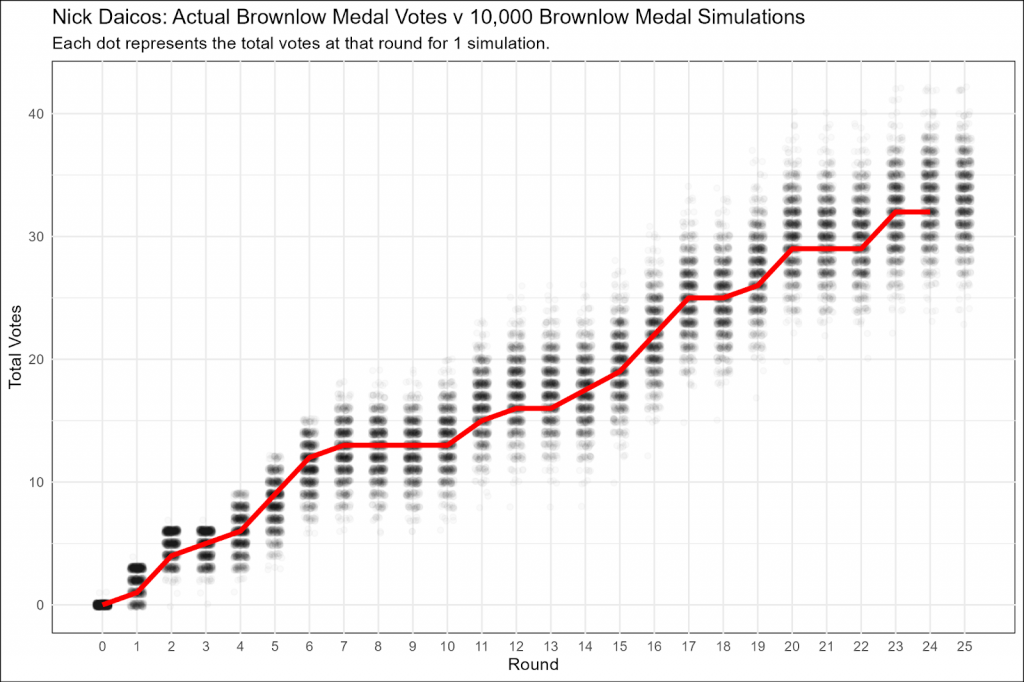

Let’s look at the favourite Nick Daicos as a demonstrative example.

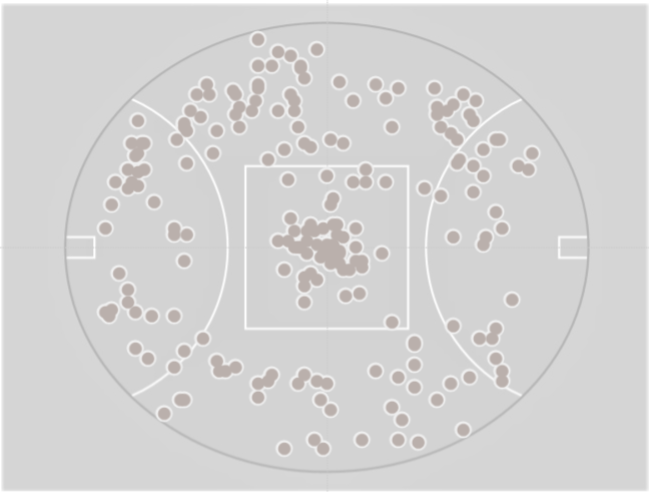

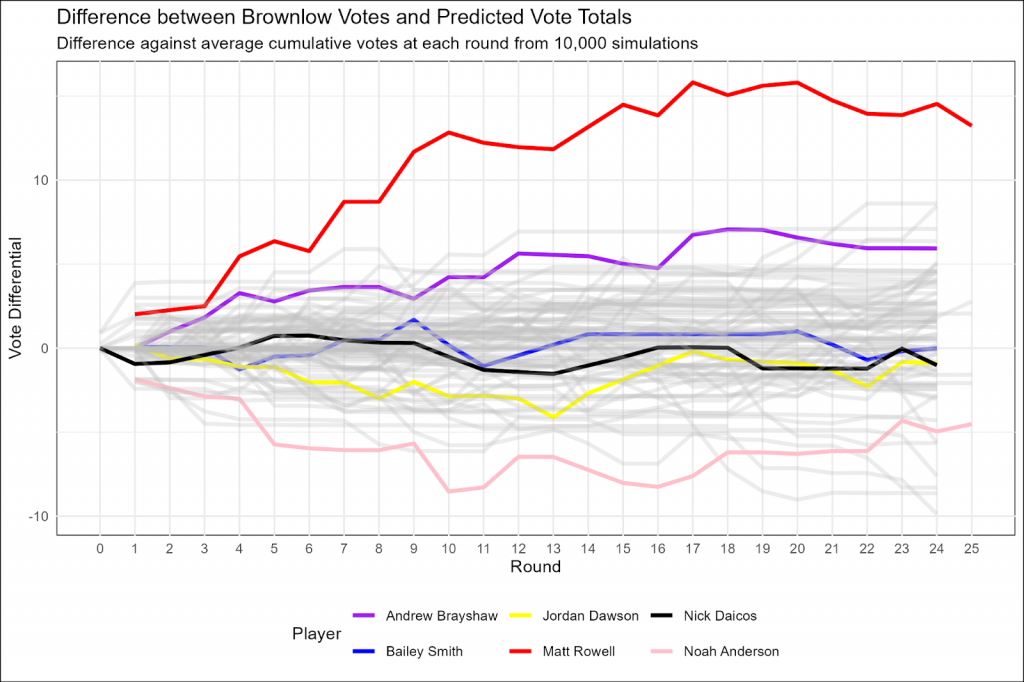

As you can see above Daicos polled exactly as predicted. His actual vote trajectory as the tally went on was well within the simulated range of votes. Across 10,000 simulations the model expected an average of 33 votes against a total of 32. In summary, the model was in the ball park of expectations for Daicos.

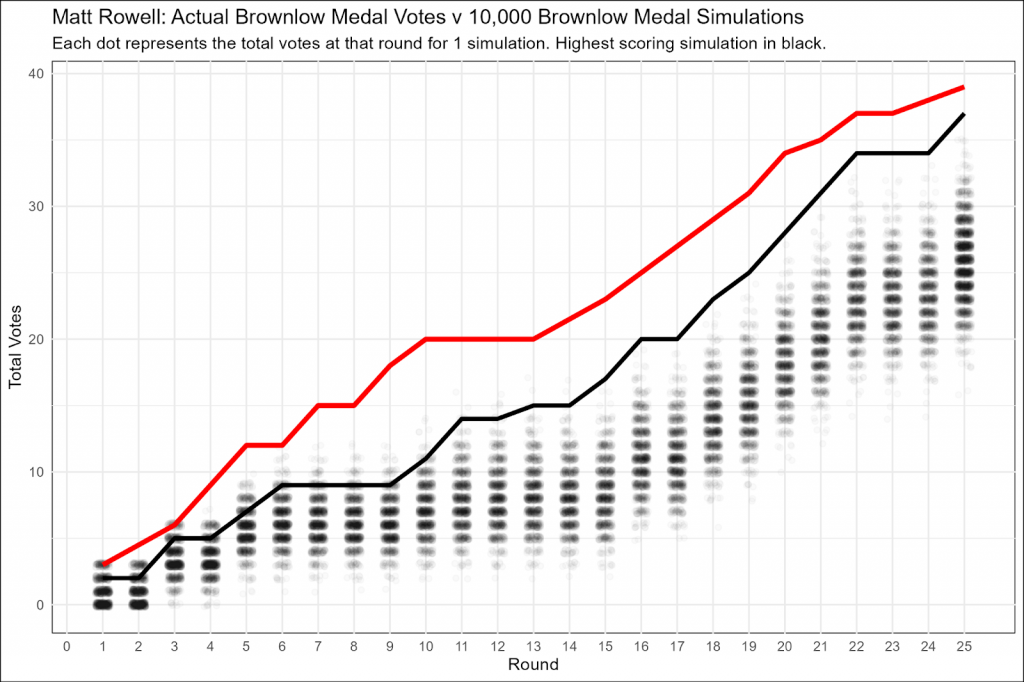

However, there was one player that smashed it out of the ballpark. Matt Rowell polled over expectation early and never looked back. The model predicted 25.8, but he polled 39 votes. That’s a whopping 13 votes above expectation.

The highest simulation that the model predicted was 37, outlined in black below. I reckon with another 10,000 or so simulations we could find one with 39 votes.

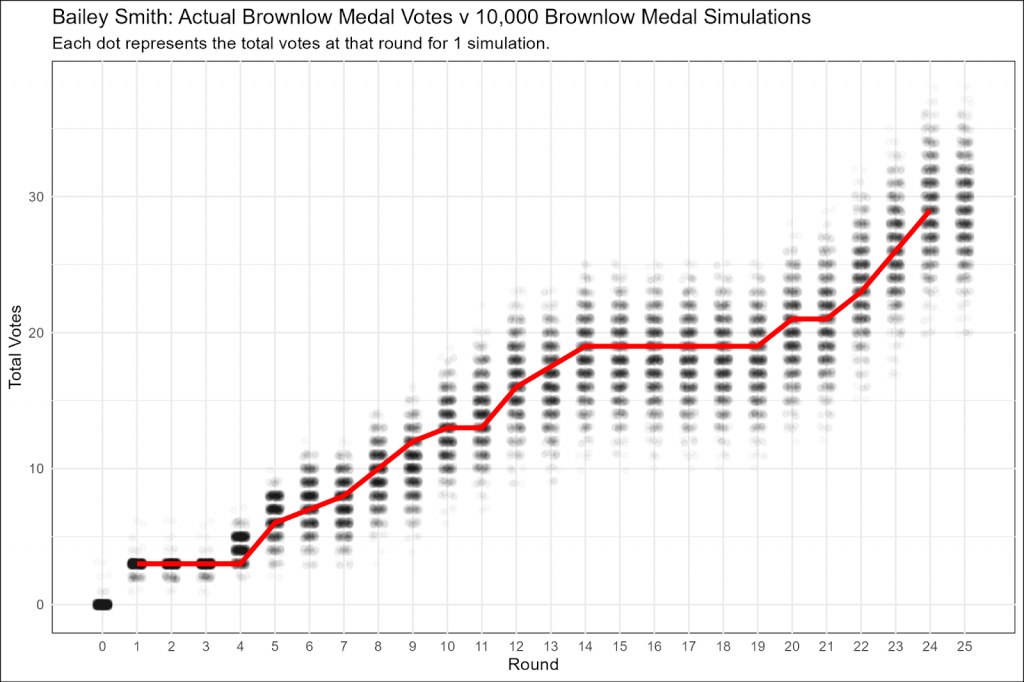

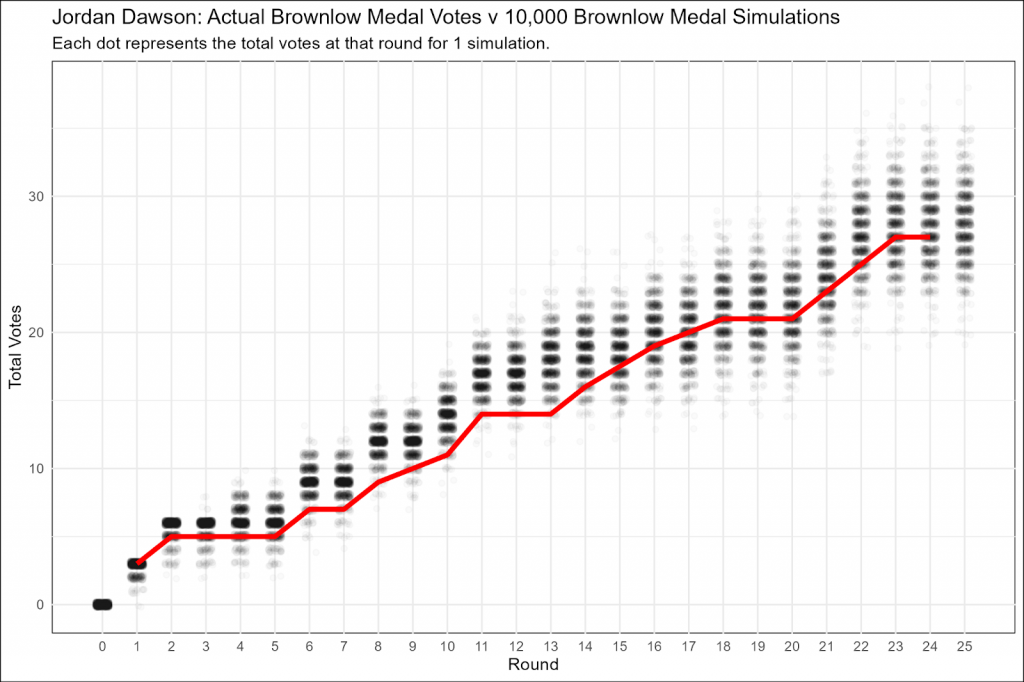

Two other Brownlow fancies fell within their simulated ranges, Geelong’s Bailey Smith and Adelaide’s Jordan Dawson couldn’t repeat the Rowell effort to overcome Daicos’s implied pre-poll lead.

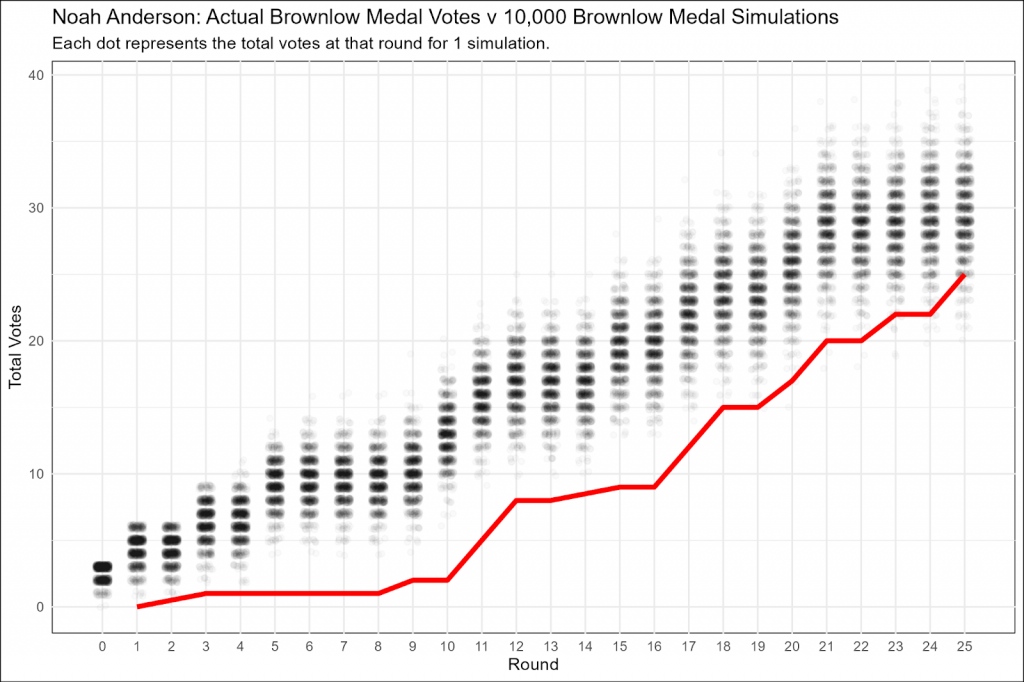

The big loser of the pre-poll favourites was Rowell’s teammate Noah Anderson with predicted and actual votes of 29.5 and 25. Anderson got a slow start to the count and couldn’t quite make up the difference to crack the top 5.

Notable mention should go to Fremantle’s Andrew Brayshaw, who polled 26 votes from an expected 20.1.

So what are the lessons we can take out of the Brownlow, and trying to work out who will win in advance?

It’s an absolute crapshoot, and in my humble opinion, that’s what makes it great.

I’ve seen people lamenting online that Rowell is a worthy winner, but simultaneously annoyed that he polled 3 votes in outlier games. The thing is, he doesn’t go on to win the Brownlow unless games like that happen!

I’d rather the tradition be kept alive with the current voting format, rather than changing it at the whims of a noisy social media contingent. Or, if you’d prefer, you can go to Wheeloratings dot com and sort by average AFL Player Ratings if you want the “True” best and fairest, but where’s the whimsy in that?

Which umpire put their foot in it when it came to Brownlow voting?

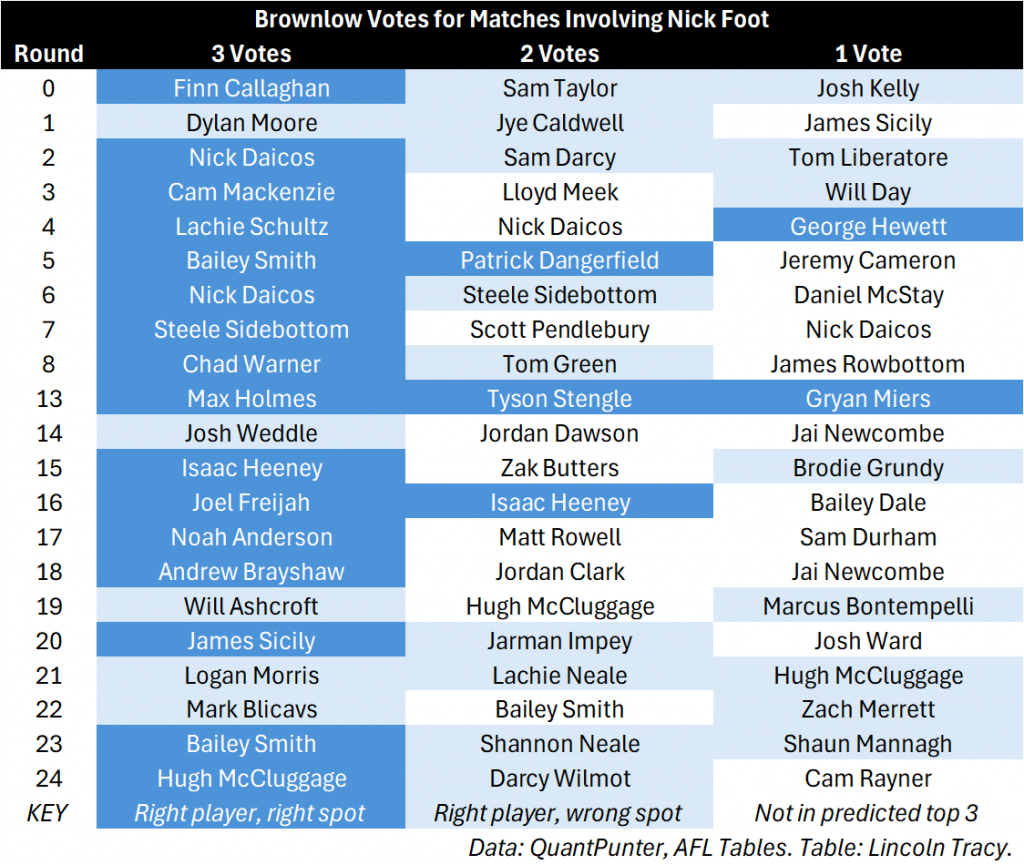

Lincoln Tracy / lincolntracy.substack.com

In February this year the AFL attracted scrutiny after giving veteran field umpire Nick Foot permission to appear on a racing program for Sportsbet, the league’s gambling partner.

Foot was one of the four field umpires who officiated the 20204 decider between Brisbane and Sydney. In addition he has been named as the emergency umpire for this weekend’s clash between Brisbane and Geelong.

The AFL claimed they were happy with the arrangement as they felt the role had nothing to do with his umpiring duties.

“He has nothing to do with football, he is not working at or around (football) with Sportsbet. He is doing content on racing, and nothing to do with football. If it (his role) had anything to do with football in any capacity, it wouldn’t have been approved,” a league spokesperson told The Age at the time.

The matter reared its head again this week during the Brownlow Medal count, where multiple group chats that I belong to wondered whether umpire Foot had anything to do with some of the “interesting” voting decisions announced on the night.

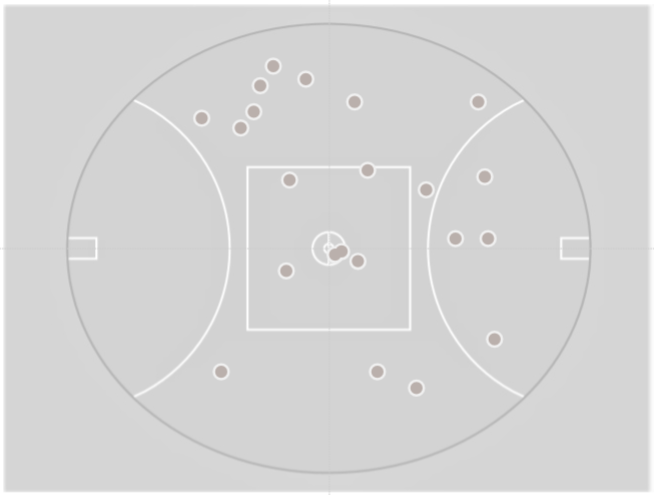

But an exploratory analysis reveals that the votes awarded in matches officiated by Mr Foot were reasonably well aligned with the consensus of 20 different predictive models collated by X account QuantPunter. Sixteen matches saw the consensus’ #1 ranked player receive the three votes (indicated by the darker blue squares), with the best on ground in the remaining five matches going to a player ranked in the top three.

And while there was only one match where the votes awarded by the umpires matched the consensus of the predictions, for the most part the umpires in these games were reasonably consistent with the consensus in terms of the top three players – save for a six-week stretch in the middle of the season.

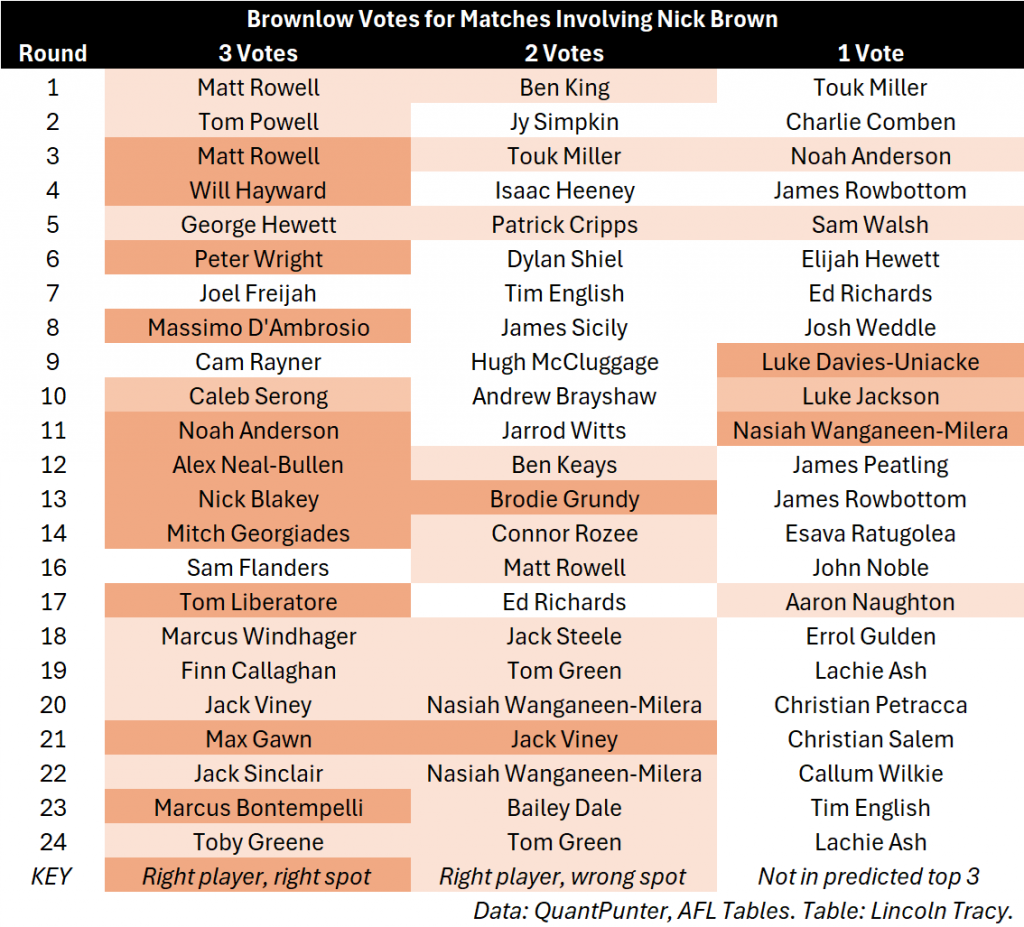

The performance of Foot and his fellow umpires appears to be more “accurate” than that of other umpires, such as Nick Brown.

The quartet of umpires involving Brown awarded the three votes to a player who was not ranked in the top three among the QuantPunter consensus data on three separate occasions, and there were many more misses with respect to the player receiving one vote.

There was even one match where none of the players who received Brownlow votes appeared in the top three among the various models (the Round 7 clash between Greater Western Sydney and the Western Bulldogs). Brown was also part of the umpiring crew that gave the three votes to Jack Viney ahead of Nasiah Wanganeen-Milera when the Saints came from nowhere to beat the Demons at Marvel Stadium in Round 20.

Select examples such as these make me wonder whether there has been a shift in recent years with how umpires determine which players have the greatest impact on a game – a line of conversation that I know has been happening in some circles – which suggests that even the most sophisticated modelling approaches will need more time and data to account for these changes.

But on the other hand, it could also be that the models are already highly accurate, and that there are some umpires who are more reliable at awarding votes than others. This inevitably leads to one of the other major conversations that has been happening this week – whether the umpires should have access to statistics when it comes time to hand out the votes.

Regardless of the underlying cause or reason, and no matter what happens in the future, there will always be arguments about who was robbed of votes and medals for years to come after football’s night of nights. But in this case, it seems that some criticisms might be more warranted than others.